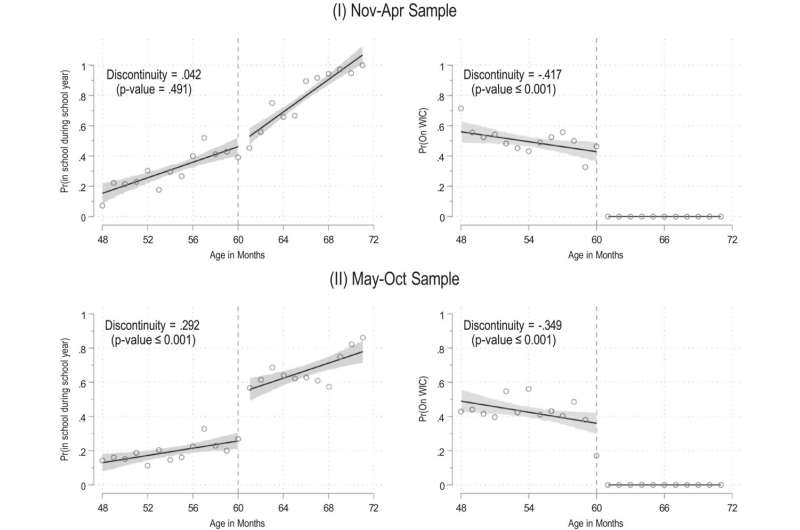

Breakdowns of probabilities of WIC participation and school attendance during the school year by age in months. Probability of attending school during the school year was based on a positive response to the NHANES question: “During the school year, [child] going to kindergarten, grade school, junior or high school?” asked by children 4 years and older. The left column shows that the probability of school attendance is not maintained at age 5 for the May–Oct sample. The right column shows, in the Nov–Apr and May–Oct samples, the probability of WIC participation among those eligible decreases at age 61 months. Credit: American Journal of Agricultural Economics (2023). DOI: 10.1111/ajae.12410

A one-year gap in WIC access may have a negative impact on the quality of some 5-year-old diets.

A new study from the University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences found that when children age out of WIC after their fifth birthday, many families are left without food assistance support for up to a year. By the time a child enters kindergarten, the nutritional quality of their diet takes about a 20% hit, according to the study.

“We were surprised to see such a large decline in nutritional quality,” said Travis Smith, author and associate professor of agricultural and applied economics. “But our results show that this program really works to increase the quality of children’s diets. Now we know that when parents lose access to WIC, they make sure their child eats the same amount of food, but they switch to lower quality food.”

WIC—the US Department of Agriculture’s special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants and children—targets nutritious foods such as whole grain breads, 100% juice, cereal and other supplemental foods. Pregnant and postpartum women, infants and children under the age of 5 are eligible.

“The focus of food assistance programs in the United States has shifted from simply providing calories to providing higher quality calories. Both components are still part of what we would consider the large umbrella of food security,” said Smith. “Without WIC, you would see a shift from free whole grains to buying refined grains, or from fresh fruits and vegetables to canned, where you might have syrups or additives.”

The study used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, a decade-long survey of medical professionals. Parents are asked to recall what their child ate over a 24-hour period, and that information is translated into a food score—the Healthy Eating Index—that accounts for the quantity and quality of food.

“As you get closer to the recommendation for each component—say, meeting the daily requirement for fruits or vegetables—your score gets higher and higher,” says Smith. “We saw children whose Healthy Eating Index scores dropped by 10 points, which equates to a 20% reduction.”

It’s a significant breakthrough, especially at such a young age, Smith said. At a young age, it is important for children to form healthy eating habits and have access to foods that can counter any food choices. This can be called “nutrition knowledge.” Essentially, it takes time and effort to get kids to enjoy certain healthy foods, like broccoli, but food aversions can develop quickly.

“If we care about helping kids eat better, and we have programs that support that goal, but we also have an arbitrary rule where kids are put off WIC and without food assistance for months or a year, we can take a step back,” Smith said. “Then all this progress you make on an individual child can be wiped out in a relatively short period of time.”

A bill that would enable states to implement a “kindergarten-roll-off” policy for WIC was proposed in the House and Senate in 2021. In 2022, the USDA Food and Nutrition Service also proposed a rule change to WIC, which would increase the cash-value of the product voucher and account for more personal and cultural food preferences.

Using the program costs specified in the proposals, Smith and his co-authors calculated the cost of expanding WIC beyond age 5 and until children are enrolled in elementary school.

WIC will cost $5.7 billion in total in fiscal year 2022, according to the USDA, and the kindergarten-roll-off would increase costs by an average of $115 million per year over the next five years under current rules—about 2 percent of the program’s costs. With the additional product vouchers, that would increase to an average of $145 million per year over the next five years—about 2.25% of program costs.

Smith hopes that this study shines a light on the potential benefits, and relative affordability, of providing WIC to children for a little longer.

“It turns out that the lowest-cost WIC participants are 4-year-olds; the most expensive are newborns because of infant formula,” Smith said. “And yet, about 40% of the program’s costs come through administrative costs, which the agency runs and pays employees.

More information:

Travis A. Smith et al, Attrition from WIC and child nutrition: Evidence from a regression design, American Journal of Agricultural Economics (2023). DOI: 10.1111/ajae.12410

Provided by the University of Georgia

Citation: Study shows kids who lose access to WIC lose nutrition (2023, July 25) retrieved on July 25, 2023 from https://phys.org/news/2023-07-kids-access-wic-nutrition.html

This document is subject to copyright. Except for any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Content is provided for informational purposes only.