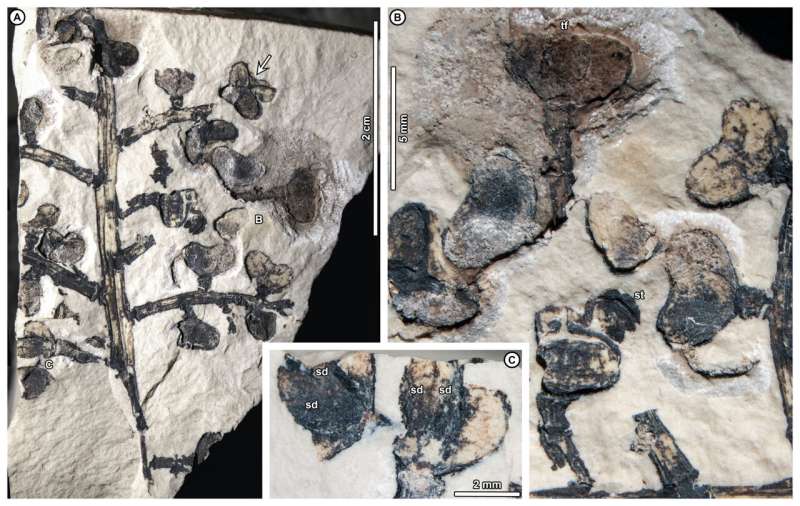

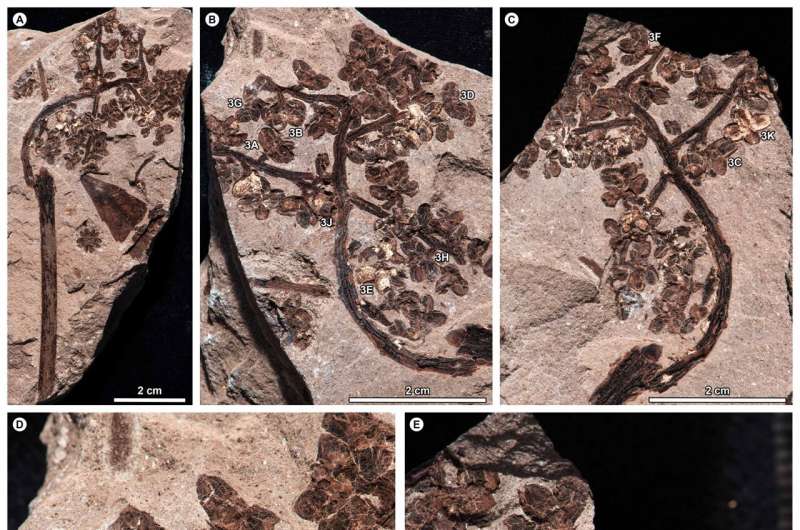

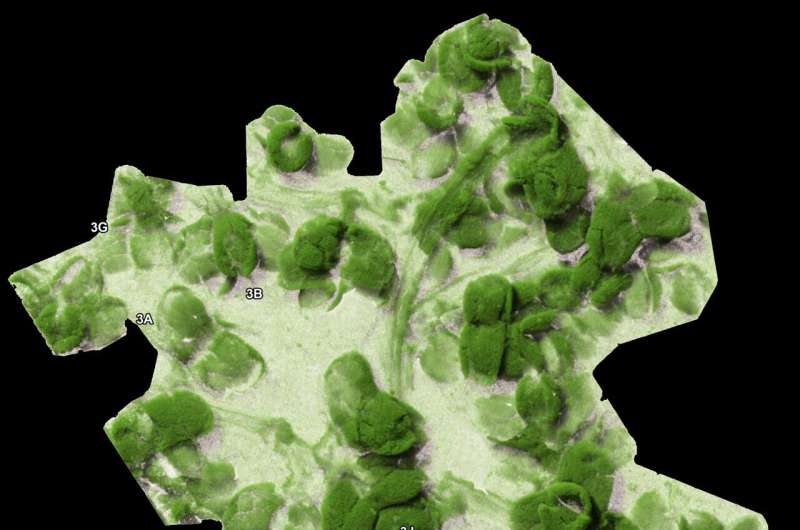

A 52-million-year-old compound infructescence fossil showing preserved fruits and seeds attached to branches, collected by the late Rodolfo Magín Casamiquela from Laguna del Hunco, Chubut province, Argentina. Plant characteristics – such as terminal fruit (tf), axile seeds (sd) and plumose stigma (st) – are currently only found in the Macaranga-Mallotus clade of the spurge family. Source: Peter Wilf

Anyone who has traveled long distances or ridden a bicycle has used a product of the spurge plant family—rubber. The spurge family, or Euphorbiaceae, includes economically valuable plants such as the rubber tree, castor oil plant, poinsettia and cassava. Newly known fossils found in Argentina suggest that a group of spurges traveled on their own tens of millions of years ago.

Because of climate changes and land movements over the millennia, a group of spurges has moved thousands of miles from ancient South America to Australia, Asia and parts of Africa, according to Penn State-led research.

Reported on American Journal of BotanyThe findings suggest that the Macaranga-Mallotus clade (MMC) of the spurge family, which includes a common ancestor and all its descendants and has long been considered to have an Asian origin, may have first appeared in South America when it was part of Gondwana—the supercontinent that includes South America, Antarctica and Australia—before spreading around the world.

“Our study provides the first direct fossil evidence of spurges in Gondwanan South America,” said Peter Wilf, professor of geosciences at Penn State and lead author of the current study, saying the finding contradicts the prevailing idea that the MMC evolved in Asia.

“But if they evolved in Asia, how in the world did they get to where we found them, in rocks in Argentina that are 50 million years old? Instead, we think that these spurges followed the moving continents from South America to Asia, to the other side of the world. yellowwood trees. Overall, this is the most dramatic evolutionary biogeography story I’ve ever seen.”

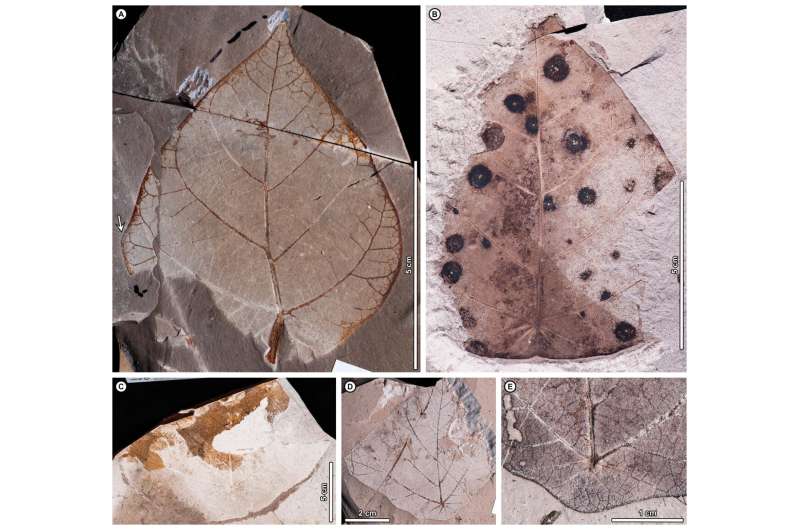

Fossil leaves with characteristics similar to many species of Macaranga. Credit: Courtesy of Peter Wilf

According to Wilf, the Euphorbiaceae are well adapted to the challenges of evolution in different environments.

“They are common in tropical rainforests in Africa, South America and especially in Asia, where if you count the number of trees in a plot, they are usually the second most common type,” he said.

“They make up most of the understory habitat that is structurally important to the rainforest and its animal life. MMC is well-known in the Asian tropics and is very common along roadsides and in burned areas. Its plants usually have large, umbrella-like leaves that provide abundant shade, and they provide nutritious seeds for animal food.”

The spurge family consists of more than 6,000 species, mostly found in the tropics but also in deserts and cold temperate zones, and there are about 400 species in the MMC alone. Because of their spread in southeast Asia and 23-million-year-old fossils previously found in New Zealand, scientists consider MMC to be an “Old World” plant group that likely originated in Asia.

The current study, based on fossils more than twice the age of New Zealand specimens, provides the first evidence of a “New World” origin for MMC spurge and adds two new species to the plant family, according to scientists.

A compound infructescence fossil showing preserved fruits and seeds attached to branches. The 52-million-year-old fossil fruits and leaves identified by researchers as belonging to the Macaranga-Mallotus clade (MMC) of the spurge family suggest that MMC, long considered to have Asian origins, may have first appeared in Gondwanan South America before spreading throughout the world. Source: Peter Wilf

Wilf and his colleagues at Argentina’s National Council for Scientific and Technological Research (CONICET) in Bariloche and the Egidio Feruglio Paleontological Museum (MEF), and Cornell University examined 11 leaf fossils and two compound infructescence fossils.

The fossils are from a site in Chubut, Argentina called Laguna del Hunco, where researchers have been collecting fossils for decades. Dating of the volcanic rocks at this site places the fossils at 52 million years old, a global warm period before the final breakup of Gondwana.

Scientists study the detailed characteristics of the leaves and fruits and compare them with living specimens. They also took CT scans of the infructescences at the Penn State Center for Quantitative Imaging. The scans pick up changes in stone density and turn them into three-dimensional images that researchers use to study parts of the fruits, including the tiny paired seeds inside the fruits that are barely visible on the surface.

The researchers found that the characteristics of fossilized fruits and leaves are found only in MMC spurge, which identifies them as two new species. They named the infructescences after the late Rodolfo Magín Casamiquela, an Argentine vertebrate paleontologist and anthropologist who collected one of the specimens, probably in the 1950s, and the leaf species after Kirk Johnson, paleobotanist and Sant Director of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History who discovered the first of the fossils90.

“MMC is widely distributed, but prior to this research they had never been found growing naturally in the Americas,” Wilf said. “This is the first time MMC has been reliably documented anywhere in the Western Hemisphere then or now.”

A CT scan of a fossil infructescence showing fruits and small paired seeds inside the fruits. A CT scan captures the changes in stone density and turns them into three-dimensional images. Source: Peter Wilf

Fossils tell a story about environmental changes, plate tectonics and biogeography, or the distribution of plants and animals around the world, said Wilf. The plants probably originated and evolved in Gondwana and began to retreat as the climate got colder over millions of years, suffering extinction in Antarctica and South America but apparently surviving in Australia, he said.

At the same time, plate tectonics broke up the Gondwanan supercontinent. Australia broke away from Antarctica more than 40 million years ago and collided with southeast Asia 25 million years ago, bringing water-demanding plants to New Guinea and the southeast Asian rainforest, the researchers said.

“We’ve seen repeatedly that we can trace a significant number of rainforest plants in Australia and Asia all the way to Argentina and Western Gondwana,” Wilf said.

“These fossils tell us how plants respond to environmental changes. If you give them time and an escape route, like in Australia as it moved from Antarctic latitudes to Asia, they can move around the world following their preferred environment and flourish. agriculture.”

“These fossils serve as a warning from the deep past, that the natural world we rely on is very resilient but cannot keep up with us. It is not too late to act and avoid the worst consequences.”

More information:

Peter Wilf et al, The first fossils of Gondwanan Euphorbiaceae reset the biogeographic history of the Macaranga-Mallotus clade, American Journal of Botany (2023). DOI: 10.1002/ajb2.16169

Provided by Pennsylvania State University

Citation: Spurge purge: Plant fossils reveal ancient South America-to-Asia ‘escape route’ (2023, July 25) retrieved July 25, 2023 from https://phys.org/news/2023-07-spurge-purge-fossils-reveal-ancient.html

This document is subject to copyright. Except for any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Content is provided for informational purposes only.